As promised, I'm posting some rough notes on the first panel I was involved with this week,

"Of/By/For." FYI these are pretty subjective impressions! I heartily welcome any comments, corrections or observations from readers or other attendees. (Note I'll also try to do a separate post on

"Bring It" in the next few days as well.)

This event involved small, engaged panel and audience on

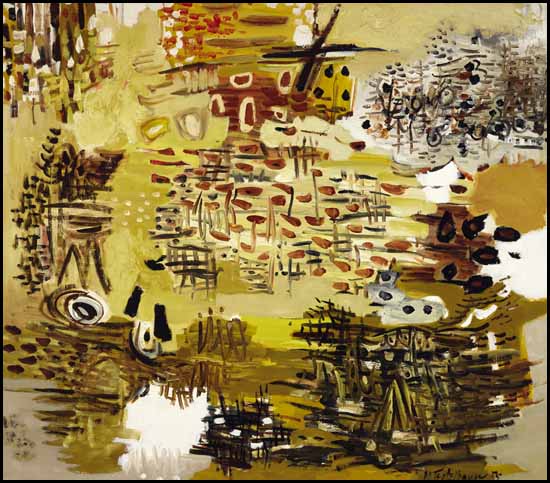

December 2 December 1 at the OCAD Graduate Gallery in Toronto. The main point of reflection was Ukrainian-Canadian artist

Taras Polataiko's recent video work In the Land of the Head Hunters, which is currently on view at

Barbara Edwards Contemporary in Toronto and previously has shown in Korea and Australia. For this video, Polataiko took

Edward Curtis's 1914 film In the Land of the Head Hunters and showed it to current residents of the BC community where Curtis had made the film. During his BC screening, Polataiko filmed the residents in the audience, as well as some of their comments afterwards.

Following screenings of Curtis' and Polataiko's film, the artist talked a bit about his past work—work that often addressed the disappearance of colonization of Ukrainian cultures. Then I spoke a bit about my assessment of the film as a general art critic, and then

Bonnie Devine spoke about the work from her perspective as a First Nations artist and curator.

My take on Polataiko's work went something like this: While the themes in Polataiko's past work and new work shared certain broad themes--like the erasure of cultural history, or the effects of colonization--I didn't find In the Land of the Head Hunters as successful or strong as his past work.

From my perspective, the reason for this is as follows: Polataiko, being a Ukrainian-Canadian person, had decades of experience and investment in Ukrainian cultural history when he started to make works about that particular culture being colonized. He is inevitably deeply engaged in that particular narrative or web of tensions and symbols, and that deep engagement, to me, really showed up in his past work, and made the works themselves deeply engaging (Polataiko's artistic skill, of course, was key too! But the engagement also really comes across.)

It was my opinion that Polataiko's lack of experience in and investment in the First Nations community and its cultural history issues resulted in the new work being much less engaged--and much less engaging. To me, the work ended up being more about distance--distance between the artist and his subjects, distance between the subjects and the 1914 film they were watching, distance between generations and cultures even today.

As a result, Polataiko's In the Land of the Head Hunters ended up, for me, feeling more like the beginning of the work than a finished work--or rather, it felt incomplete, and not in a good way. (Polataiko did confirm he is continuing on projects and collaboration with this First Nations community, so maybe I'll have more to look at in the future on this point.)

When the question of "Well, should artists be allowed to make work about different cultures? Should there be limit setting or box ticking?" came up, I clarified my position this way--when an artist is working in a culture or subculture different from their own, they actually need to

expand the limits of their practice,

not limit them. They have to understand that the same old approaches or techniques or production schedules will not necessarily be equal to the task. They need to understand they have to invest more energy and more intellect and more time into the work to even get an inkling of the rich understandings they can draw upon so instantly when working within their own culture.

Granted, there are some lucky geniuses out there, across all artistic genres, who can make entering another cultural realm--be it gender based, nation based, language based, or ability based--seem effortless. But those geniuses are far and few between. For most of us, it takes more effort, time and thought to intelligently, sensitively and convincingly work outside our own sociocultural niche.

So, that was my take....

For my part, I found Bonnie Devine's perspectives really enlightening as well. She reflected that the people she saw in Polataiko's film are/represent "those who have not died." They are survivors. And when those survivors are watching the 1914 film, they are naturally not critiquing all the film artifices that Polataiko might. Rather, they are seeing their uncles, aunts, grandparents, loved ones--those who have died; those who have not survived. (For many in that audience, it was their first time seeing the Curtis film.)

Devine, along with artist/curator

Gerald McMaster, who was in the audience, also noted how Polataiko's shots of current-day residents in some ways replicated the profiles of Curtis' famed (and much critiqued) photography of First Nations people. She also noted how much the adults in Polataiko's film avoided meeting the gaze of the camera--a survival strategy, perhaps, or remnant of that historical legacy.

Overall, I felt Devine was able to open up the consideration of the film, and I wish I had taken more notes on her comments because they were really insightful (as well as less judgmental of the work than yours truly, but hey, I guess that's what I'm supposed to bring). McMaster also provided a lot of interesting perspectives as well, positing that what we were seeing in Polataiko's film was two timespans floating past each other, with a big space between them.

The conversation continued for some time with quite engaged commentary and questions from the audience. I bet that panel organizer

Rose Bouthillier, an artist and curator herself, will likely do more interesting stuff in the future.

And... just to reiterate, this post is a very, very, very partial record of the proceedings, so I appreciate any clarifications, questions, links, criticisms or comments readers might be willing to share.

Image of notepad from PSDRockstar